Transfer & Mobility – 2015

This second report on transfer and mobility, examines multiple transfer pathways for the cohort of students who started postsecondary education in 2008. It reveals how student enrollment patterns that involve multiple movements among two or more institutions and across state boundaries has become the new normal, demonstrating the need for a comprehensive view of student transfer and mobility to inform education policymaking and institutional improvement efforts. The report also provides discussion comparing the 2008 cohort’s outcomes to those of the 2006 cohort (analyzed in our first transfer and mobility report, Signature Report 2).

Signature Report 9 Data Extra: Transfer and Mobility Rates by State

This Data Extra presents the state-level breakdown of the Transfer and Mobility national numbers presented in our ninth Signature Report, “Transfer & Mobility: A National View of Student Movement in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2008 Cohort” published in July 2015.

Posted on November 3, 2015.

Suggested Citation: Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Wakhungu, P.K, Yuan, X., & Harrell, A. (2015, July). Transfer and Mobility: A National View of Student Movement in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2008 Cohort (Signature Report No. 9). Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

About This Report

AUTHORS

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center

- Doug Shapiro

- Afet Dundar

Project on Academic Success, Indiana University

- Phoebe Khasiala Wakhungu

- Xin Yuan

- Autumn T. Harrell

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Don Hossler, Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at Indiana University Bloomington; the members of the Project on Academic Success team, Sarah B. Martin, and Youngsik Hwang; and Vijaya Sampath from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center for their efforts, thoughtful comments and suggestions. Of course, any remaining errors or omissions are solely the responsibility of the authors.

SPONSOR

This report was supported by a grant from the Lumina Foundation. Lumina Foundation, an Indianapolis-based private foundation, is committed to enrolling and graduating more students from college — especially 21st century students: low-income students, students of color, first-generation students and adult learners. Lumina’s goal is to increase the percentage of Americans who hold high-quality degrees and credentials to 60 percent by 2025. Lumina pursues this goal in three ways: by identifying and supporting effective practice, through public policy advocacy, and by using our communications and convening power to build public will for change. For more information, log on to www.luminafoundation.org.

Executive Summary

Of the 3.6 million students who entered college for the first time in fall 2008, over one third (37.2 percent) transferred to a different institution at least once within six years. Of these, almost half changed their institution more than once (45 percent). Counting multiple moves, the students made 2.4 million transitions from one institution to another from 2008 to 2014.

This report defines student transfer and mobility as any change in a student’s institution of enrollment irrespective of the timing, direction, or location of the move, and regardless of whether any credits were transferred from one institution to another. The transfer rate reported here considers the student’s first instance of movement to a different institution, before receiving a bachelor’s degree and within a period of six years. For those students who began at two-year public institutions, we also include transfers that happened after receiving a degree at the starting two-year institution.

Going beyond broad national transfer rates, this report shows students’ enrollment patterns across two-year and four-year, public and private institutions, and also examines the distribution of transfers and mobility across state lines and over multiple years. Such a comprehensive look makes the findings useful for state and institutional policymakers as well as for college administrators and the general public. With a better understanding of student transfer and mobility, institutional policymakers will be amply equipped to advise their students on different enrollment pathways. Transfer rates across state lines will help state policymakers understand the implications of student mobility for state-level policies, in particular for outcomes-based funding policies.

Findings of the report provide evidence of the role played by community colleges in students’ pathways, even though the students often do not earn associate’s degrees. Nearly a quarter of the students who started at a community college transferred to a four-year institution within six years. Yet, only 3.2 percent of this cohort, roughly one in eight of those who transferred, did so after receiving a credential from their starting institution, either a certificate or an associate’s degree. The vast majority transferred without a degree.

This proportion has shrunk from the Research Center’s first transfer and mobility report, released in 2012. That report, which looked at students who started in fall 2006, found that one in five transfers from two-year to four-year institutions were post-degree. The higher proportion of students transferring without an associate’s degree may create a growing case for reverse transfer initiatives currently being pursued in many states. These initiatives facilitate the transfer of student credits back to two-year institutions that may be able to award a degree.

Other findings include:

- Student mobility often involves out-of-state transfers. Nearly one in five transfers among students who started in two-year public institutions, and nearly a quarter of transfers from four-year public institutions, occurred across state lines.

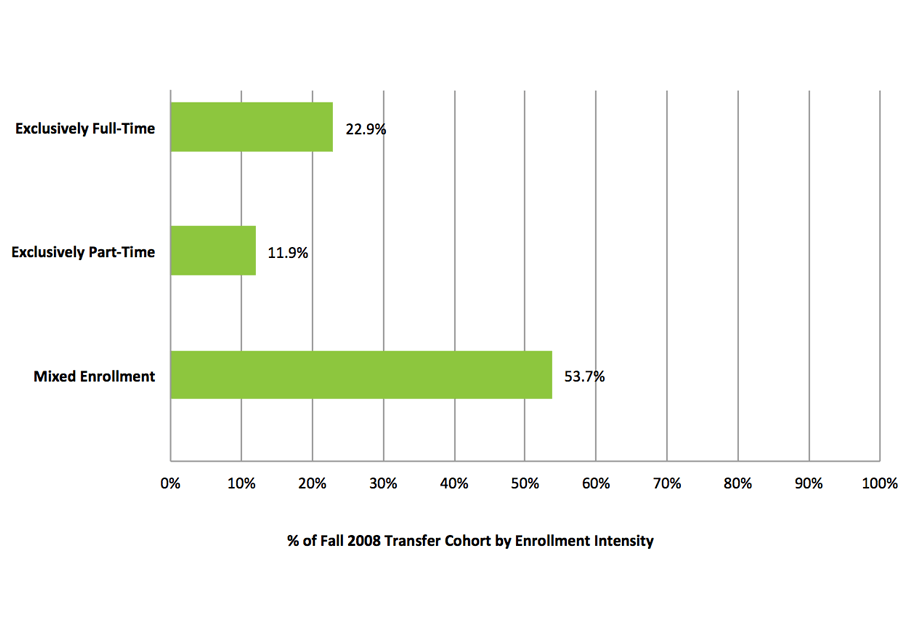

- Mixed enrollment students (those who enrolled both full- and part-time) had the highest transfer and mobility rates at 53.7 percent. Changing institutions and changing enrollment statuses both appear to be strategies that students employ in reaction to their changing circumstances.

- Exclusively part-time students, who are typically more geographically constrained and most likely to stop out of college altogether, had the lowest transfer rate (11.9 percent).

- Two-year public institutions are the top mobility destination for students who start in four-year institutions. More than half (51.3 percent) of those transferring from a four-year public institution moved to a two-year public institution. Over 40 percent of those who transferred from four-year private institutions headed to community colleges.

- A quarter of all student mobility from four-year institutions to community colleges consisted of summer swirlers, who returned to their starting institution in the following fall term. This strategy was found, in an earlier Clearinghouse report, to be correlated to higher degree completion rates at the starting four-year institution.

As our findings demonstrate, the picture of postsecondary enrollment, transfer, persistence, and completion is very complex, which highlights the importance of broadening the definitions of both student success and institutional effectiveness. The increased attention to student outcomes and degree attainment at the national and state levels are likely to lead to new accountability measures for postsecondary institutions that will need to go beyond the first-time full-time cohorts that institutions are used to tracking. Looking at the outcomes of all students – non-traditional students who enroll part-time or switch their enrollment status from full-time to part-time and vice-versa as well as transfer-in and transfer-out students – will be beneficial for public policymaking and individual students.

Introduction: Transfer and Mobility as Integral to Students’ Education Pathways

Since we published our groundbreaking first report on transfer and mobility (Hossler et al., 2012), much has changed — including perceptions. These days, few observers of higher education in America hold a linear view of postsecondary access and success. The diverse pathways that students take to achieve their academic goals are well acknowledged in the research and higher education community.

Student demographics have also shifted during this time, with the new cohorts having more adult learners, fewer full-time enrollments, and students who are generally more sensitive to the cost of their education. Indeed, changes have occurred across the higher education landscape as more states move toward outcomes-based funding and institutions offer more online courses.

As student enrollment patterns involving multiple movements among two or more institutions and across state boundaries become the new normal (Marling, 2013), more than ever, a comprehensive view of student transfer and mobility that captures these complex movements is needed to inform education policymaking and institutional improvement efforts. In response to this need, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center is releasing this new transfer and mobility report examining multiple transfer pathways for the cohort of students who started postsecondary education in 2008.

In the research literature, the complex phenomenon of student mobility has been defined in diverse terms, including transfer, swirling, and double-dipping, etc. (Adelman, 2006; McCormick, 2003), as well as from different perspectives, such as vertical or upward transfer (Dougherty & Kienzl, 2006; Doyle, 2009; Eagan & Jaeger, 2009). Other transfer patterns, such as reverse transfer (transfer from four-year institutions to two-year institutions or, as lately defined, the process by which students combine credits from both two-year and four-year institutions toward an associate’s degree from the two-year institution) or lateral transfer (transfer from one four-year institution to another or from one two-year institution to another), have also been documented in recent years (Goldrick-Rab & Pfeffer, 2009; U.S. Department of Education, 2001; Dongbin et al., 2012). However, because of data availability, most empirical research is restricted to only one transfer pattern at a time. The findings of most of these studies are also limited to just one institution, one state, one time period (e.g., fall to fall), or one enrollment type (e.g., full time).

DEFINING TRANSFER AND MOBILITY

Student mobility is an important phenomenon to examine because it plays a significant role in students’ degree completion, an indicator of student success. It can facilitate baccalaureate degree attainment for community college students who transfer to four-year institutions (Townsend, 2007). Students may transfer from four-year institutions to two-year institutions — to complete additional coursework at lower cost. Students who transfer from a two-year to a four-year institution may also transfer credits back to the starting two-year institution to receive a two-year degree before finishing the requirements for a bachelor’s degree. Many students may also make a lateral transfer to find a better institutional fit or a program that more closely meets their interests.

This report defines student transfer and mobility as any change in a student’s institution of enrollment irrespective of the timing, direction, or location of the move, and regardless of whether any credits were transferred from one institution to another. Our intent is to illustrate the complexity of student movement among institutions. The report includes transfer and mobility across institutions, sectors, and states — even if these movements happen over summer terms, after a period of nonenrollment, or if the movements later prove to have been temporary. Our report also includes all students, those enrolled exclusively full time, exclusively part time, and with mixed enrollment, without attempting to discern intent to earn a degree at either the starting or the destination institution.

The transfer rate reported here considers the student’s first instance of movement to a different institution, before receiving a bachelor’s degree and within a period of six years. For those students who began at two-year public institutions, we also include transfers that happened after receiving a degree at the starting two-year institution. This exception was made because of the importance of vertical transfer as a key success outcome for so many students at community colleges. While for many community college students a certificate or an associate’s degree is the end goal with no intent to transfer, in many states completion of an associate’s degree as part of the pathway to a bachelor’s degree is encouraged through policies that guarantee junior standing to students who complete an associate’s degree (ECS, 2014). Moreover, the common usage of transfer terminology for students who start in two-year institutions includes transfer after receiving an associate’s degree.

Various studies of transfer among students at four-year institutions consider short-term movement as inconsequential, or “casual course-taking,” treating students who later return to the starting institution as not having moved at all. Our definition of transfer and mobility includes these types of “multi-institutional attendance” (Adelman, 2006). This is because, in part, we consider only students’ enrollments at institutions, not course credits earned, whether credits were accepted by the destination institution, or, if so, how many credits were accepted. We do, however, highlight the “summer swirl” pattern (i.e., transfers among students who started at four-year institutions that happen only in summer followed by a return to the starting four-year institution).

Going beyond broad national transfer rates, this report shows students’ enrollment patterns across two-year and four-year, public and private institutions, and also examines the distribution of transfers and mobility across state lines and over multiple years. Such a comprehensive look makes the findings useful for state and institutional policymakers as well as for college administrators and the general public. With a better understanding of student transfer and mobility, institutional policymakers will be amply equipped to advise their students on different enrollment pathways. Transfer rates across state lines will help state policymakers understand the implications of student mobility for state-level policies, in particular for outcomes-based funding policies.

Exploration of transfer and mobility is also relevant given the recent focus on the potential role of community colleges in the national college completion agenda. For example, initiatives that offer free community college for students who maintain good academic standing (e.g., Chicago Star Scholarship, Tennessee Promise) could affect the college-going patterns for today’s postsecondary students, possibly increasing transfer into and out of community colleges.

WHAT TO FIND IN THIS REPORT

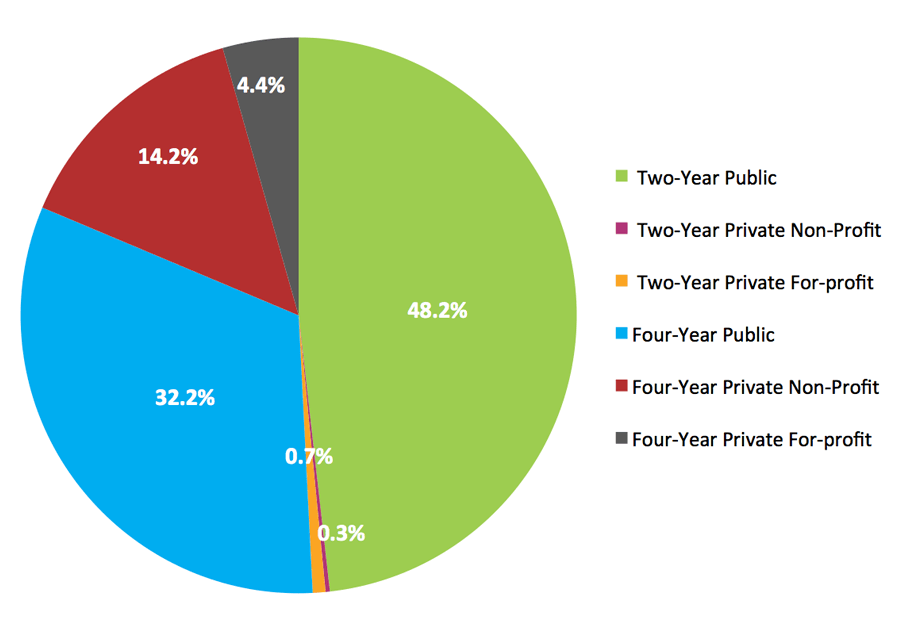

Focusing on the cohort of first-time students who began their postsecondary studies at U.S. colleges and universities in fall 2008, this report examines student transfer and mobility patterns over six years, through summer 2014. We begin with over 3.6 million students, the full cohort of first-time students across all types of institutions (Figure I1).

Figure I1. Students’ First Enrollment by Institution Type, Fall 2008 Cohort*

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 1.

The findings in this report provide an in-depth analysis of the first instance of transfer or mobility. The tables and figures present:

- The prevalence of transfer and mobility nationwide overall and by gender, sector, and control of both the starting and destination institution;

- Transfer and mobility for exclusively full-time, exclusively part-time, and mixed-enrollment students, showing rates and timing of first transfer by initial enrollment intensity and institution type;

- In-state and out-of-state mobility by institution sector and control;

- Transfer and mobility trajectories and pathways, specifying institutional origins and destinations;

- Timing of the first instance of transfer or mobility, broken out by sector and control of both the starting and destination institution;

- Transfer from a two-year to a four-year institution with and without first earning an associate’s degree;

- Lateral transfer from one two-year to another two-year institution, or from one four-year to another four-year institution, with or without an eventual return to the starting institution;

- Transfer from a four-year to a two-year institution, with or without an eventual return to the four-year institution; and

- Second, third, or further mobility, or serial transfers.

Tables 13-19 of Appendix C provide additional detail on the number of students who transferred more than once.

Results

SECTION 1: OVERALL TRANSFER AND MOBILITY: FALL 2008 FIRST-TIME STUDENT COHORT

A total of 3,629,429 students enrolled in postsecondary education at U.S. colleges and universities for the first time in fall 2008. Among this cohort, 37.2 percent enrolled in a different institution at least once during 2008-2014. Women had a slightly higher transfer rate than men (39.0 and 36.8 percent, respectively) (Appendix C, Table 3).

The findings represent students who, according to the Clearinghouse data, enrolled between fall 2008 and summer 2014 in an institution different from the one where they began in fall 2008. In other words, in this report, student transfer and mobility is defined as any change in a student’s institution of enrollment regardless of whether any credits were transferred from one institution to another. Only consecutive enrollments at different institutions were considered in the study. Students who were concurrently enrolled in their starting institution and another institution were not counted as transfers.

The results emphasize the destination and timing of students’ first instance of transfer, regardless of what occurred after that point on the students’ postsecondary pathways. Therefore, transfer students may have continued studies at their new institution, returned to their starting institution, moved on to a third institution, completed a degree, or stopped out after transferring within or outside the study period. The transfer rate includes students who transferred from a two-year public institution after receiving a credential at the starting two-year institution. Post-degree mobility is not captured for students who started in any other of type of institution.

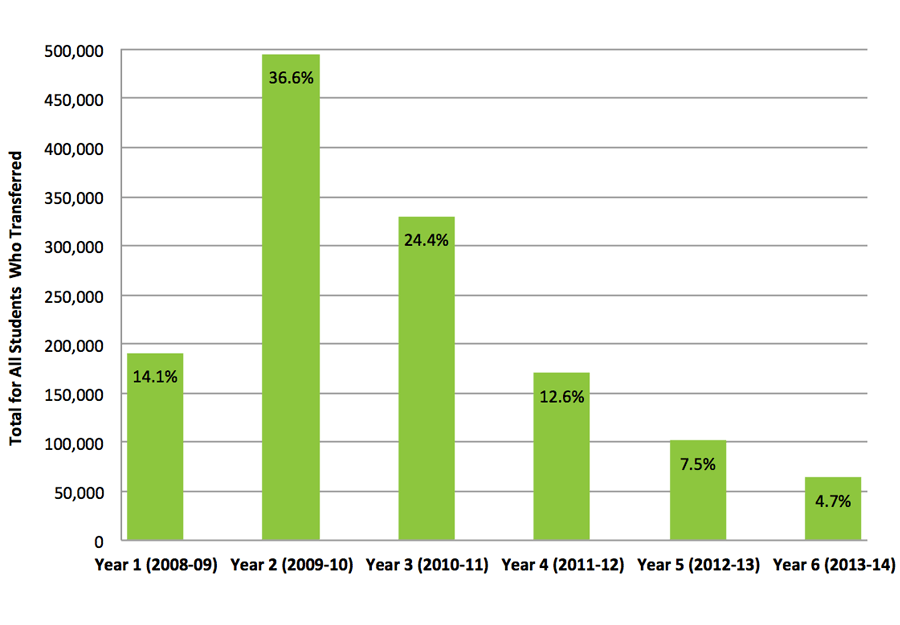

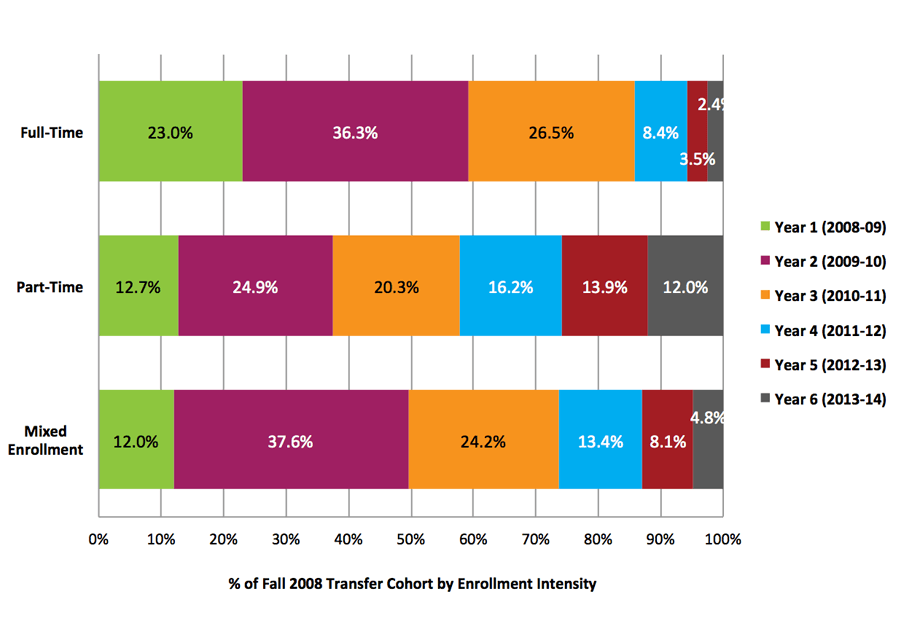

Figures 1 through 5 present the timing of first transfers as well as overall transfer patterns by enrollment intensity and institutional sector.

Among all students who transferred, the most prevalent time for their first transfer was during the second year (36.6 percent) of college, with another quarter of students (24.4 percent) transferring in their third year (Figure 1).

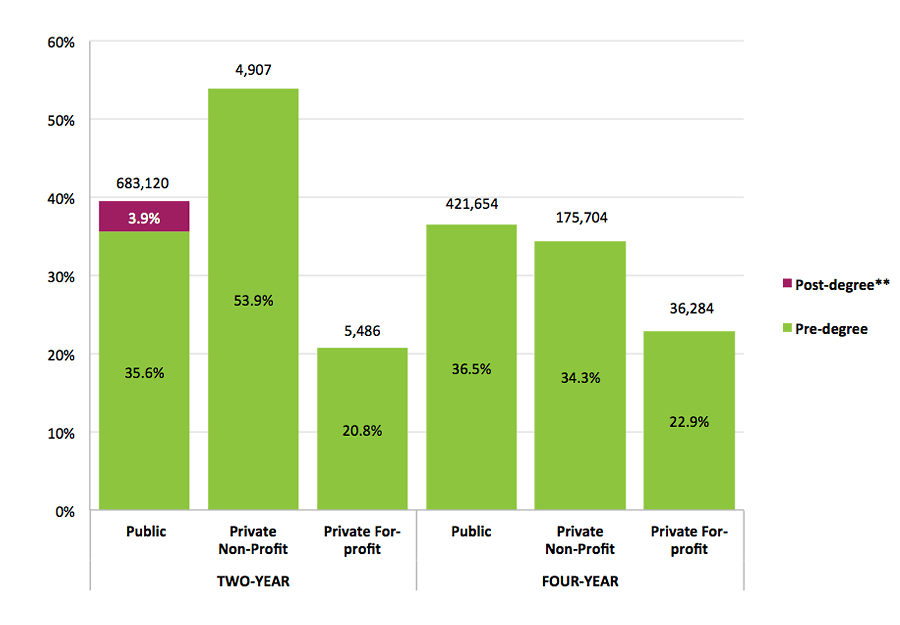

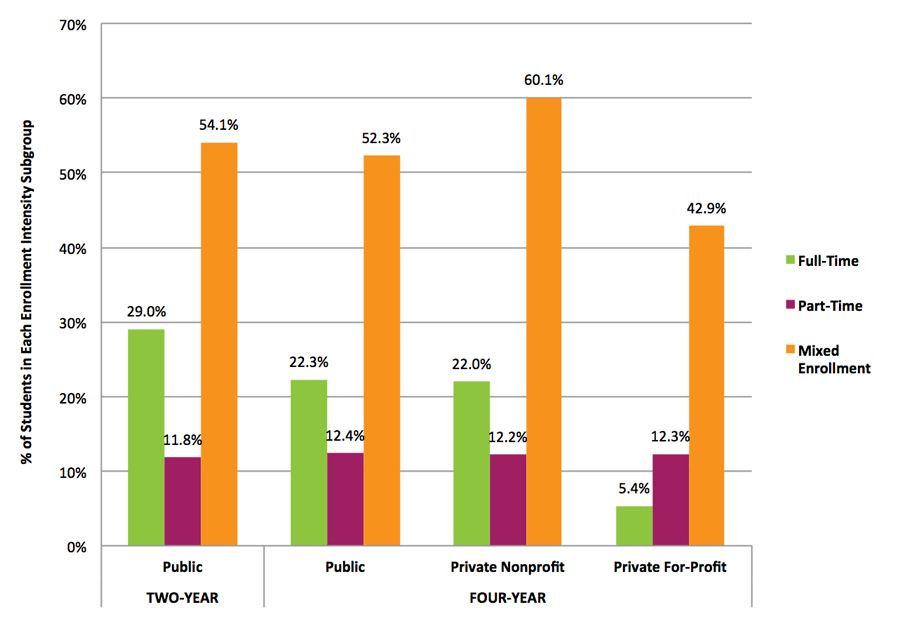

Figure 2 highlights the prevalence of transfer by sector and control of students’ starting institutions. Two-year public institutions had a transfer rate of 39.5 percent, including a small percentage (3.9 percent) of students transferring after receiving a credential at the starting community college. Among those who started at four-year institutions, those who started at four-year public institutions had the highest transfer rate (36.5 percent) followed by those who started at four-year private nonprofit institutions (34.3 percent) and private for-profit institutions (22.9 percent).

Breakdowns by enrollment intensity demonstrate that changing institutions was common among mixed-enrollment students, with more than half of this group (53.7 percent) transferring to another institution at least once. Transferring among exclusively full-time students was also prevalent, with more than one in five students in this group doing so at least once in six years. Just over a tenth (11.9 percent) of part-time students transferred at least once during the same period (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Timing of First Transfer or Mobility 2008-2014, All Transfer Students, Fall 2008 Cohort*

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 7a.

Figure 2. Six-Year Transfer and Mobility Rates by Sector and Control of Starting Institution*

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 4.

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 4.

**Post-degree transfers are counted only for students who started in 2-year public institutions.

Figure 3. Six-Year Transfer and Mobility Rates By Enrollment Intensity, Fall 2008 Cohort*

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 15.

Figure 4. Timing of First Transfer or Mobility by Enrollment Intensity, Fall 2008 Cohort*

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix B, Table 8.

Figure 5. Transfer and Mobility Rates by Enrollment Intensity and Institution Type*

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 17, Table 18, & Table 19.

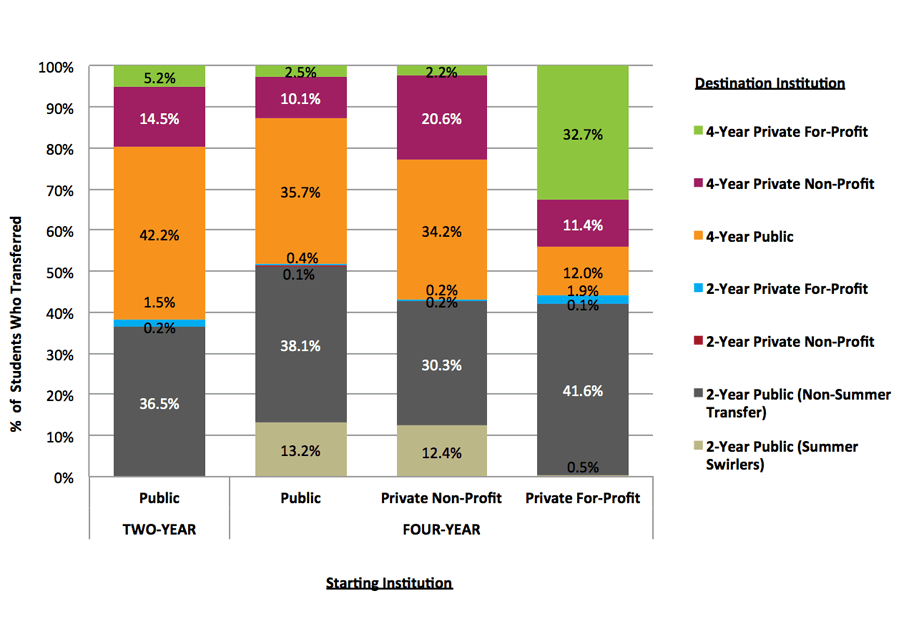

SECTION 2: OVERALL TRANSFER AND MOBILITY PATTERNS: STARTING AND DESTINATION INSTITUTIONS

Figure 6 shows the breakdown of transfer destinations of students who began in each institution type. For students who started in four-year institutions, two-year public institutions were a top destination. More than half of all students (51.3 percent) who transferred from four-year public institutions transferred to two-year public institutions. Those who started at four-year private nonprofit and four-year private for-profit institutions had equally high transfer rates to two-year public institutions (42.6 and 42.0 percent, respectively). Among students who began at two-year public institutions, most transfers were to four-year public institutions (42.2 percent), while 36.5 percent were lateral to another two-year public institution. These results point to the importance of community colleges as destinations that serve students transferring in large numbers from every kind of institution.

It is important to note that transfers from four-year institutions to community colleges may involve students who are likely to be taking courses at community colleges only for a short time as part of a continuing baccalaureate program, as well as those who may be changing programs and enrolling long term in community colleges.

Figure 6. Destination of First Transfer or Mobility by Sector and Control of Starting Institution, Fall 2008 Cohort

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 6a and Table 6b.

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 6a and Table 6b.

SECTION 3: TRANSFER AND MOBILITY ACROSS STATES

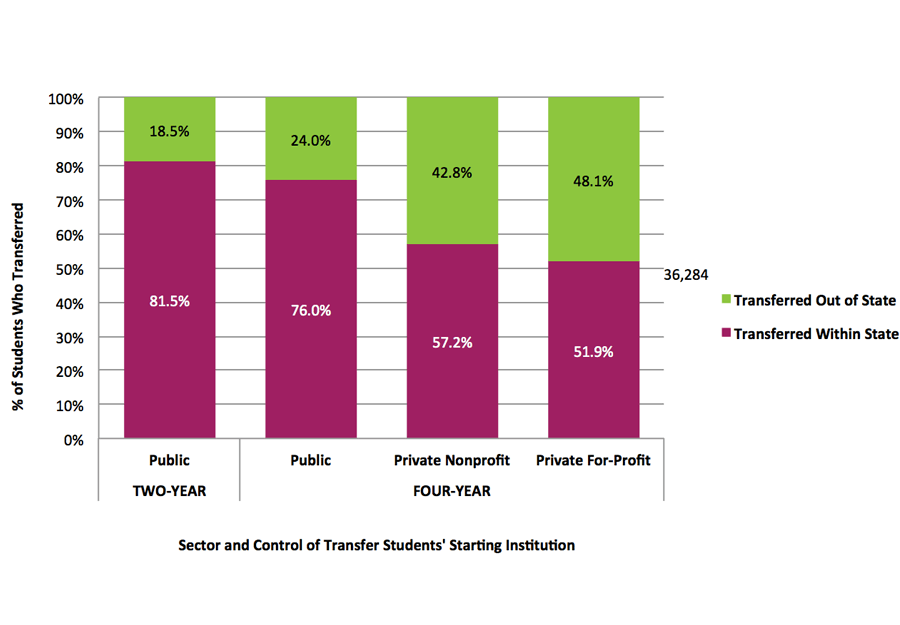

Figure 7 shows the prevalence of transfer within and across state lines. The focus is on whether the destination institution is in the same state as the starting institution, regardless of the student’s state of residence. Students who started their postsecondary education at multistate institutions (i.e., institutions with branches in more than one state) were excluded from this analysis. Specifically, several for-profit institutions fall into the multistate category and, thus, are not included in Figure 7.

As Figure 7 demonstrates, moving to a school in a different state is not uncommon for students in all types of institutions. Even within the public sector, about one in five transfer students (18.5 percent) who started in two-year institutions and about one quarter of those from four-year institutions (24.0 percent) moved to an institution in a different state.

Figure 7. In-State and Out-of-State Transfer and Mobility by Sector and Control of Starting Institution, Fall 2008 Cohort*

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 9.

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 9.

SECTION 4: TRANSFER AND MOBILITY RATES BY INSTITUTIONAL SECTOR

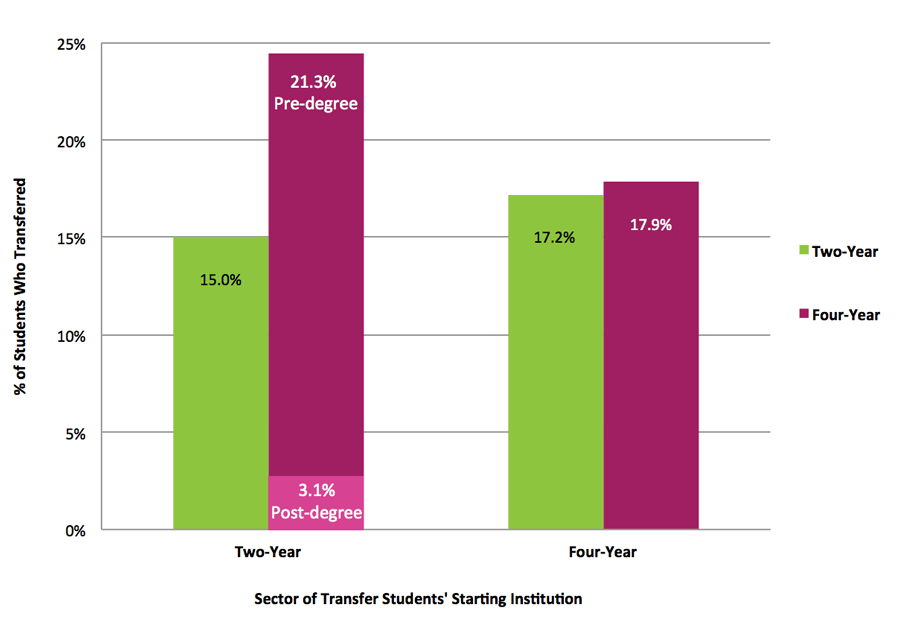

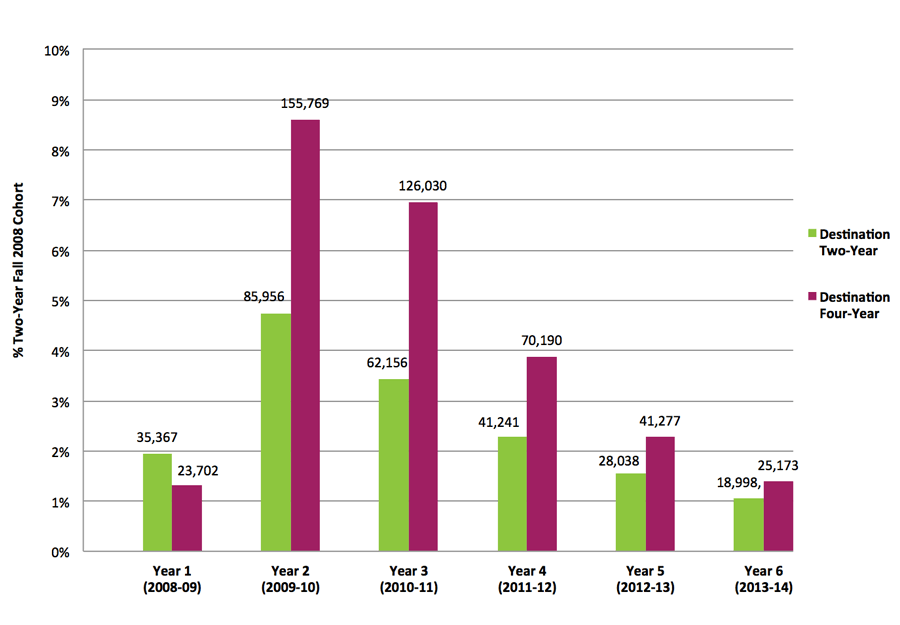

Figures 8, 9, and 10 show transfer and mobility rates as well as the timing of the initial transfer by the sector of both the starting and destination institutions. Figure 8 is a comprehensive view of transfer rates by sector of the first transfer destination among students who began in two-year and four-year institutions. Among students who started at two-year institutions, the transfer rate to four-year institutions was 24.4 percent (including 3.9 percent post-degree transfers), while the rate of lateral transfer (transfer to another two-year institution) was 15.0 percent.

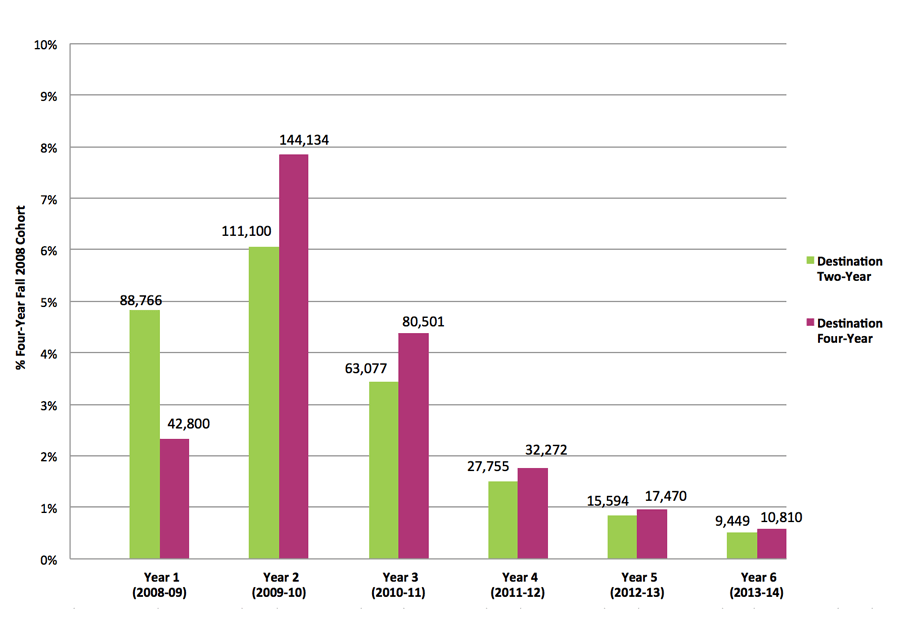

For students who started at four-year institutions, the rate of transfer to a two-year institution was similar to the lateral transfer (a move to another four-year institution), 17.2 percent and 17.9 percent, respectively.

Figure 9 shows the transfer rates of students who began at two-year institutions in fall 2008, focusing on the timing of transfer by sector of destination institution. The majority of transfer activity from two-year to four-year institutions took place during the second and third years of enrollment (8.6 percent and 7.0 percent of the starting cohort, respectively). It should be noted that the analysis of the timing of the transfer does not account for the period of nonenrollment. For example, the second year of enrollment indicates a second year since the student started in fall 2008, not two years of continuous enrollment.

Figure 10 shows the transfer rates of students who started at four-year institutions in fall 2008, focusing on the timing of the transfer by the sector of the destination institution. Comparable to results shown for two-year institutions, transfers most often occurred early in students’ academic career. Although first-year transfers from two-year institutions were relatively uncommon, students who started at four-year institutions showed significant transfer activity during the first year of enrollment. In particular, transfer from four-year to two-year institutions was highest in the first and second years of enrollment (4.8 percent and 6.1 percent, respectively).

Figure 8. Total Transfer and Mobility Rate by Sector of Destination Institution, Students in the Fall 2008 Cohort Who Began at Two-Year and Four-Year Institutions*

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 10.

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 10.

Figure 9. Timing of First Transfer or Mobility by Sector of Destination Institution, Students in the Fall 2008 Cohort Who Began at Two-Year Institutions*

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 10.

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 10.

Figure 10. Timing of First Transfer or Mobility by Sector of Destination Institution, Students in the Fall 2008 Cohort Who Began at Four-Year Institutions*

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 10.

*This figure is based on data shown in Appendix C, Table 10.

Discussion

HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE REPORT

Over a third of all first-time students (37.2 percent) transferred to or enrolled in a different institution at least once within six years and before receiving a bachelor’s degree.

Women had a slightly higher transfer rate than men (39.0 and 36.8 percent, respectively). Transfer rates for students in two-year public, four-year public, and four-year private nonprofit institutions ranged from 34.3 percent to 39.5 percent, while the rates for students who started in four-year private for-profit institutions were much lower (22.9 percent).

Of those who transferred, almost half (45 percent) changed their institution more than once. The transfer rate of the cohort, combined with the frequency of transfers, depict a complex picture of movement through multiple institutions while students pursue their academic goals.

Differences in transfer and mobility rate from the previous study

The cohort studied in this report entered colleges and universities in fall 2008, at the peak of economic recession. Compared to the previous year’s cohort, these students were more likely to be older, enroll part-time, and enroll in community colleges and for-profit institutions. In our most recent college completion report, we observed a small decline in the six-year completion and persistence rates for the fall 2008 cohort compared to the previous year’s cohort (Shapiro et al., 2014).

Given these changes, it is perhaps surprising that we did not find any large recession effects on the overall transfer rate: after adjusting for methodological changes — a longer measurement period (six years instead of five), inclusion of post-degree vertical transfers for students who started in community colleges, and the inclusion of former dual enrollment students in the starting cohort — the overall transfer and mobility rate was similar to the rate we reported for the fall 2006 cohort (33.1 percent) in 2012 (Hossler et al., 2012). We observed a notable difference, however, in transfer and mobility from community colleges, which we discuss below.

Another difference stems from changes to Clearinghouse data collection procedures over the years included in this study. Until summer 2011, the Clearinghouse did not record data on students who were enrolled in summer terms at less-than-half-time status. In addition, data for summer students with full-time status and half-time status were collected from participating institutions only on an optional basis. These changes, combined with the methodological changes, contributed to the increase in the measured rate of multiple transfers from 25 percent of all mobile students transferring two or more times in the 2006 cohort to 45 percent in this report.

STUDENT TRANSFER AND MOBILITY TO AND FROM TWO-YEAR PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS

Vertical Transfer and Mobility

Of all first-time students who started at a two-year public institution, 24.4 percent transferred to a four-year institution during the study period and another 15.0 percent made a lateral move to another two-year institution.

About four percent of two-year starters transferred after receiving a credential, either a certificate or an associate’s degree, at their starting institution, including 3.2 percent who transferred to a four-year institution. In our previous reports we consistently observed that more students transfer to a four-year institution without a two-year credential than with one (Hossler et al., 2012; Shapiro et al., 2013). For example, our first study on student transfer and mobility (Hossler et al., 2012) showed that a total of 25.1 percent of students who started in two-year public institutions transferred to a four-year institution, with one in five of those who transferred doing so after receiving a two-year credential. Fewer two-year starters who transferred to a four-year institution from the fall 2008 cohort did so post-degree: only one in eight. Given that this cohort started in college in the Great Recession, it is possible that more students may have enrolled in two-year institutions seeking a terminal credential. On the other hand, more students may have enrolled in two-year schools because of affordability concerns, planning to transfer to a four-year institution after accumulating lower-cost credits, with no intent of receiving a two-year degree. The high proportion of pre-degree transfers within the overall mobility pathway from two-year to four-year institutions (87 percent) makes this explanation highly plausible.

The shrinking post-degree transfer pathway provides a compelling reason for institutions and policymakers to pursue reverse transfer initiatives, which enable students to combine their credits from both two-year and four-year institutions in order to be awarded an associate’s degree by the two-year institution. Some two-year and four-year schools have programs to facilitate this process and a few states have reverse transfer legislation in place (Anderson, 2015; Garcia, 2015). Reverse transfer initiatives have the potential to reduce the numbers of students who end up in the “some college no degree” category after transferring to a four-year institution without a two-year credential and then failing to complete the bachelor’s degree (Shapiro et al., 2014).

Two-Year Public Institutions as the Most Prevalent Transfer Destination for Students Who Started in Four-Year Institutions

The results show that two-year public institutions are the top transfer destination for students who start in four-year institutions. More than half (51.3 percent) of those who transferred from four-year public institutions moved to a two-year public institution. Among those who transferred from four-year private nonprofit institutions, 42.7 percent enrolled in a two-year public institution. The proportion for transfers from four-year private for-profit institutions was similar (42.0 percent). Community colleges have long been considered an important postsecondary entry point for students who would not be able to attend college otherwise. This finding demonstrates that community colleges are also an essential part of postsecondary pathways, regardless of where the student begins.

TRANSFER AND MOBILITY RATES BY ENROLLMENT INTENSITY

New in this year’s mobility report is the analysis of transfer rates in combination with enrollment intensity patterns over the entire six-year student pathway. Not surprisingly, students who change institutions are also the most likely to change from full-time to part-time status, and vice-versa. Mixed enrollment students, those who enrolled both full- and part-time during regular (non-summer) terms, accounted for the largest proportion of the fall 2008 cohort (52.4 percent), and they had by far the highest transfer and mobility rate (53.7 percent). Exclusively part-time students, who are typically more geographically constrained and most likely to stop out of college altogether, had the lowest transfer rate (11.9 percent). For mixed enrollment students, switching to a different enrollment status and/or changing their institution seem to be linked strategies, adopted in reaction to their changing circumstances. This flexibility appears to help them make continuous progress towards their goal, as mixed enrollment students also have a much higher completion rate than part-time students (Shapiro, Dundar, Yuan, Harrell, & Wakhungu, 2014).

The timing of transfer and mobility reveals an interesting pattern when linked to enrollment intensity: exclusively full-time students transferred overwhelmingly in the first three years of enrollment (85.8 percent of all transfers). For mixed enrollment students, higher proportions of transfers (a total of 61.8 percent) happened in the second and third years of enrollment than in the first, fourth, fifth, and sixth years.

Compared to other enrollment intensity categories, the timing of first transfer for students enrolled exclusively part-time was more evenly spread across the study period, with many exclusively part-time students making their first move to another institution in later years: 42.1 percent of all first transfers for these students occurred in years four, five, and six. It is important, however, to bear in mind that these time frames are more likely to include possible periods of non-enrollment or stopout than those of full-time or mixed enrollment students. This finding may reflect the demands and interests of this student group, who may often need to manage full-time employment in addition to attending college, stretching out their pathways to completion. Change of institutions for exclusively part-time students, therefore, seems to be more likely to happen because of life circumstances necessitated by family or employment reasons.

TRANSFER AND MOBILITY FOR STUDENTS IN FOUR-YEAR INSTITUTIONS

More than one-third of students who started in four-year public institutions (36.5 percent) changed their institution at least once within six years. As mentioned earlier in this section, just over half of transfers (51.3 percent) from four-year public institutions went to two-year public institutions. Even after removing summer swirlers from this mobility pattern (13 percent of transfers from four-year public institutions, made up of those who enrolled in a two-year institution only in summer and returned to their starting four-year institution in the following fall), the remaining transfers to community colleges would still represent the largest single destination for students who started in four-year public institutions.

Students who began in four-year private nonprofit institutions had a slightly lower overall transfer rate than those who started in four-year public institutions (34.4 percent), and the community college share of the destination institutions is markedly smaller (42.7 percent). Removing the summer swirlers in this case leaves only 30 percent of the transfers going to two-year public institutions, which is lower than the share who transferred laterally to four-year public institutions (34.2 percent). Overall, students who started in four-year private nonprofit institutions were more likely to have a lateral transfer to another four-year institution than those who began in four-year public institutions (57.0 percent vs. 48.3 percent).

As a top transfer destination for students who start in four-year institutions, community colleges appear to contribute to those students’ success in more than one way. Summer swirlers may have had financial or academic reasons for taking summer courses at two-year institutions, or geographic reasons — they may simply have relocated or returned home for the summer. Whether these students later return to their starting four-year school or not, the prevalence of community colleges along the various enrollment pathways of students who began their postsecondary education at four-year institutions reveals students’ intentional strategies to take advantage of a range of institutional options in order to enhance their progress towards educational goals.

OUT-OF-STATE TRANSFER AND MOBILITY

Our findings show that students often move to another state while changing the institution. While the proportion of transfers that happened out of state was much higher for students who started in four-year private nonprofit (42.8 percent) and four-year private for-profit institutions (48.1) than for those who started in two-year and four-year public institutions, the latter groups also had sizable out-of-state mobility rates. Nearly one in five transfers (18.5 percent) among students who started in two-year public institutions and one in four (24.0) transfers among students who started in four-year public institutions went to an institution in a different state.

As these findings demonstrate, student mobility is not limited by state-lines. However, the ability to track student movement and completion at the state and institution level often stops at state borders when pursued through state longitudinal data systems. As more states move towards performance-based funding, it is more important than ever for states and institutions to be able to measure the outcomes of their transfer-out students.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICYMAKING

In fall 2008, 3.6 million first-time students entered college. Within the next six years these students made 2.4 million transitions from one institution to another: some transitioned only once and others multiple times. Since our last report on transfer (Hossler et al., 2012) much has changed: today few hold a linear view of college access and success. The picture of postsecondary enrollment, transfer, persistence, and completion is very complex, which highlights the importance of broadening the definitions of both student success and institutional effectiveness.

Given the argument that faster progress towards a credential make college completion more likely for students (Bowen, Chingos, & McPherson, 2009) and the call for shorter completion timelines (Complete College America, 2011), this report especially highlights the mobility of students as they pursue various paths during their academic career. The effects of mobility, in particular change of the institution more than once, on degree completion is an under-researched topic. While mobility can often result in loss of credits (Monaghan and Attewell, 2014), simply recommending that students do not change their institution does not seem to fit the reality of today’s students, particularly given the prevalence of transfer, and the many potential reasons for it suggested by this report. Instead, both starting and destination institutions should work together to better inform and advise students, and to make these transitions smoother and more hurdle-free.

Finally, the increased attention to student outcomes and degree attainment at the national and state levels are likely to lead to new accountability measures for postsecondary institutions that will need to go beyond the first-time full-time cohorts that institutions are used to tracking. Looking at the outcomes of all students — non-traditional students who enroll part-time or switch their enrollment status from full-time to part-time and vice-versa as well as transfer-in and transfer-out students — will be beneficial for public policymaking and individual students. We hope that the mobility patterns described in this report lead institutions to recognize the important role they play in individuals’ academic and career goals, however long or short each student’s window of enrollment at the institution may be.

References

Adelman, C. (2006, February). The tool box revisited: Paths to degree completion from high school through college. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Vocational and Adult Education.

Anderson, L. (2015). Reverse Transfer: The path less traveled. Retrieved from http://www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/01/18/77/11877.pdf

Bowen, W. G., Chingos, M. M., and McPherson, M. S. (2009). Crossing the Finish Line: Completing College at America’s Public Universities. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Complete College America. (2011). Time is the enemy. Retrieved from http://www.completecollege.org/docs/Time_Is_the_Enemy.pdf

Dongbin K, Saatcioglu, A., and Neufeld A. (2012). College departure: Exploring student aid effects on multiple mobility patterns from four year institutions. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 42(3).

Dougherty, K. J., & Kienzl, G. S. (2006). It’s not enough to get through the open door: Inequalities by social background in transfer from community colleges to four-year colleges. Teachers College Record, 108(3), 452-487.

Doyle, W. R. (2009). Impact of increased academic intensity on transfer rates: An application of matching estimators to student-unit record data. Research in Higher Education, 50, 52-72.

Eagan, K. M. & Jaeger, A.J. (2009). Effects of exposure to part-time faculty on community college transfer. Research in Higher Education, 50, 168-188.

Education Commission of States [ECS](2014). Transfer and articulation: All state profiles. Retrieved from http://ecs.force.com/mbdata/mbprofallRT?Rep=TA14A

Garcia, S. (2015). Reverse transfer: The national landscape. Retrieved from http://occrl.illinois.edu/

Goldrick-Rab, S. & Pfeffer, F. T. (2009). Beyond access: Explaining socioeconomic differences in college transfer. Sociology of Education, 82, 101-125.

Hossler, D., Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Ziskin, M., Chen, J., Zerquera, D., & Torres, V. (2012, February). Transfer and mobility: A national view of pre-degree student movement in postsecondary institutions (Signature Report No.2). Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Marling, J. L. (2013). Navigating the new normal: Transfer trends, issues, and recommendations. New Directions for Higher Education, 162, 77-87.

McCormick, A. (2003). Swirling and double-dipping: New patterns of student attendance and their implications for higher education. New Directions for Higher Education, 121, 13-24.

Monaghan, D. B & Attewell, P. (March, 2015). The community college route to the bachelor’s degree. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, Online publication doi: 10.3102/0162373714521865.

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Ziskin, M., Chiang, Y. Chen, J., Torres, V., & Harrell, A. (2013, August). Baccalaureate Attainment: A National View of the Postsecondary Outcomes of Students Who Transfer from Two-Year to Four-Year Institutions (Signature Report No. 5). Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Yuan, X., Harrell, A., Wild, J., Ziskin, M. (2014, July). Some College, No Degree: A National View of Students with Some College Enrollment, but No Completion (Signature Report No. 7). Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Yuan, X., Harrell, A. & Wakhungu, P.K. (2014, November). Completing College: A National View of Student Attainment Rates – Fall 2008 Cohort (Signature Report No. 8). Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Townsend, B. K. (2007). Interpreting the influence of community college attendance upon baccalaureate attainment. Community College Review, 35(2), 128-136.

U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. High School Academic Curriculum and the Persistence Path Through College, NCES 2001–163, by Laura Horn and Lawrence K. Kojaku. Project Officer: C. Dennis Carroll. Washington, DC: 2001.

Appendix A: Methodological Notes

OVERVIEW

This report describes the transfer activity of the fall 2008 cohort of first-time college students across the U.S. for six years through August 2014. The results presented show patterns in students’ enrollment in multiple postsecondary institutions, focusing on the sector and control of starting institutions (the colleges and universities in which students first enrolled) and of destination institutions (the institutions to which students first transferred). Public, private non-profit, and private for-profit institutions are considered separately in the results, as are two- and four-year institutions in each of these categories. The designation “two-year institution” is used broadly to identify institutions offering both associate’s degrees and less than two-year degrees and certificates.

In addition to overall transfer pathways by institution type, the report includes results on transfer disaggregated by gender; exclusively full-time, exclusively part-time, and mixed enrollment students; an overview of transfer activity within and between states; and multiple views on the timing of student transfer by institution type and enrollment intensity.

NATIONAL COVERAGE OF THE DATA

The National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) is a unique and trusted source for higher education enrollment and degree verification. Since its creation in 1993, the participation of institutions nationwide with NSC has steadily increased. Currently, NSC data include more than 3,600 colleges and 96 percent of U.S. college enrollments. NSC has a 22-year track record of providing automated student enrollment and degree verifications. Due to its unique student-level record approach to data collection, the Clearinghouse data provide opportunities for robust analysis not afforded by more commonly used institution-level national databases.

Because NSC’s coverage of institutions (i.e., the percentage of all institutions in the NSC data) is not 100 percent for any individual year, weights were applied in this study by institution sector and control to better approximate enrollment figures for all institutions nationally. Using all IPEDS Title IV institutions as the base study population, sampling weights for enrollments at each institution type were calculated using the inverse of the rate of coverage for that sector (see Appendix B for further details).

The enrollment data used in this report provide an unduplicated headcount for the fall 2008 first-time-in-college student cohort and are not limited by institutional and state boundaries. Moreover, because the data are student level, researchers can use them to link concurrent as well as consecutive enrollments of individual students at multiple institutions, a capability that distinguishes NSC data from national data sets built on institution-level data. For instance, in the National Center for Education Statistics’ (NCES) Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) — one of the most widely used national data sets in postsecondary education research — concurrent enrollments remain unlinked and, therefore, are counted as representing separate individuals.

COHORT IDENTIFICATION, DATA CUT, AND DEFINITIONS

Focusing on the cohort of first-time students who began their postsecondary studies at U.S. colleges and universities in fall 2008, this report examines student transfer and mobility activity over six years through summer 2014. In order not to exclude or misrepresent the pathways of students who were enrolled in college preparatory summer study, students who began their postsecondary studies in either summer or fall 2008 were included in the study. However, the summer 2008 enrollment records were not included in the analysis; fall 2008 enrollments were considered the first enrollment for all students selected for the cohort. To further verify that only first-time undergraduate students were included in the study, the Clearinghouse data were used to confirm that students included showed no previous college enrollment at any institution during the four years prior to 2008 and had not previously completed a degree at any institution at any time prior to 2008.

In defining the study cohort, it was necessary to identify a coherent set of first enrollment records that would as closely as possible represent a starting point for the fall 2008 cohort of first-time-in-college students. With this goal in mind, the researchers excluded enrollment records that were either (a) not clearly interpretable within the study’s framework and data limitations or (b) inconsistent with the experiences of first-time college enrollment and college transfer that were the focus of the analysis. Students who showed concurrent enrollments (defined as enrollment at two or more institutions in which the term start and end dates overlapped by at least one day) in the fall 2008 term were excluded from the study. Students were also excluded if they had no fall 2008 enrollments lasting 21 days or longer. Students whose first enrollment was outside the U.S. or in U.S. territories (e.g., Guam, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands) were excluded from the study cohort. However, students who transferred to postsecondary institutions located outside the U.S. or in U.S. territories after the first term (i.e., after fall 2008) were included in the study.

The study cohort was defined, therefore, as students who fulfilled all of the following conditions, according to the Clearinghouse data:

- enrolled in fall 2008 (defined as any term with a begin date between August 11-October 31, 2008, inclusive); if the institution had no term begin date during this period, then between July 14 and August 10, 2008, inclusive;

- did not have a previous enrollment record between June 1, 2004, and May 31, 2008, unless the previous enrollment record was before the student turned 18 years old (dual enrollment);

- did not receive any degree or certificate from a two- or four-year institution prior to fall 2008;

- enrolled in just one institution in fall 2008; and

- enrolled in at least one term in fall 2008 that was longer than 21 days.

In addition to criteria for the inclusion of students in the cohort, the researchers applied several decisions related to the inclusion of individual enrollment records, term to term. Enrollment records showing an end-date preceding the begin-date (a “negative” term length) and records exceeding 365 days in length were considered the result of reporting error and excluded from the analysis. In these cases, only the out-of-range enrollment record was excluded, while the student remained in the cohort.

Finally, enrollments in multistate institutions — those with branches in more than one state — were excluded from the state-to-state transfer analysis because these institutions typically report all student enrollments from a central location, regardless of the actual location of instruction. It should be noted that many large for-profit institutions fall into the multistate category.

CONCURRENT ENROLLMENT

As mentioned previously, NSC data provide an unduplicated headcount of U.S. college enrollments during each term, which allows following individuals across concurrent enrollment. In preparing data for this report, students with concurrent enrollments during the fall 2008 term were excluded from the cohort. Students with concurrent enrollments after the first term, however, were retained. Each instance of concurrent enrollment occurring after fall 2008 was examined and a primary enrollment record was selected from among the concurrencies for use in the transfer analysis. Concurrent enrollment was defined in this stage as two or more enrollment records in which the term start/end dates overlapped by 30 days or more. Primary enrollments were selected using the following decision rules:

- Continuing enrollment over changing enrollment: Continuing enrollment at the institution where the student had been enrolled during the previous term was selected over an enrollment at a different institution. This rule produces conservative results on the prevalence of transfer, since some students may use concurrent enrollments as a way of transitioning from one institution to the next.

- Earlier term begin-date over later begin-dates: If a student was concurrently enrolled in two or more new institutions and no longer enrolled in his or her previous institution, the enrollment record with the earliest begin-date was selected as primary.

DEFINING TRANSFER

In this report, transfer is defined as enrollment subsequent to the fall 2008 term in an institution different from the one in which the student was enrolled during fall 2008 (the starting institution). This is provided that the student was not concurrently enrolled at the starting institution and had not already completed a degree or certificate, unless the starting was a two-year institution. For those who started at two-year institutions, change of the starting institution can take place before or after receiving a two-year credential. These types of enrollment patterns are defined as transfers regardless of subsequent enrollments (e.g., completion, returning to the starting institution, etc.).

Therefore, even if a student enrolled at a new institution for a short time then returned to the starting institution, the enrollment pattern is still categorized as a transfer. The results presented in this report capture the extent to which students change institutions at least once (i.e., they identify the first instances of student transfer).

DATA LIMITATIONS

The data limitations in this report center mainly on data coverage, the methods used for cohort identification, and the definition of key constructs, as outlined above.

In fall 2008, representation of private, for-profit institutions in the Clearinghouse data was lower than that of other institution types, with the proportion of coverage ranging from quite low for two-year private for-profit colleges (14 percent of institutions, weighted by IPEDS enrollments) to moderately low for four-year private for-profit institutions (66 percent). Participation of two-year private non-profit institutions was also relatively low, at just 35 percent. For fall 2008, NSC data nevertheless offered near-census national coverage (96 percent) of public institutions, and an overall coverage rate of 92 percent of U.S. postsecondary enrollments.

In order to correct for differences in coverage rates, enrollment data were weighted, as explained previously, according to the level and control of each student’s starting institution in fall 2008. This accounts for the likelihood of finding a student in the NSC data in the original cohort, but not for the likelihood of finding the student again if he or she transfers to another institution. The frequency of transfer is thus underestimated in this report, particularly transfer to institutional sectors with lower coverage rates. That is, a student who transfers to a for-profit institution is less likely to be counted as transferred than a student who transfers to a public institution. In data explorations of this question, the researchers determined that overall transfer rates were underestimated for all starting institution categories and underestimated to a slightly higher extent for for-profit institutions.

It is important, furthermore, to acknowledge limitations resulting from the cohort identification methods used in this report. Because NSC data do not include designations for class year, the researchers identified first-time undergraduate students via two indirect measures:

- no previous college enrollments recorded in StudentTracker® going back four years and

- no previous degree awarded in NSC’s historical degree data.

Given these selection criteria, the sample for this report may include students with more than 30 Advanced Placement (AP), International Baccalaureate (IB), or dual enrollment credits who, despite first-time status, would not be considered first-year students. Moreover, because of inconsistencies in the historical depth of NSC degree data records, it is possible that a small number of graduate students are also included in the study cohort.

Selection of “primary enrollment records” from students’ concurrent enrollments introduces possible error because of the risk of selecting a primary enrollment record that is “wrong” (i.e., not what the student considered his or her primary enrollment).

The transfer definition used in the analysis for this report gives rise to further limitations. Because of the definition, transfer results shown in the report include students who returned to their starting institution after enrolling in a different institution, regardless of how long the student was enrolled in the “new” institution. For example, students “swirling” or taking classes at a different institution during the summer were identified as transfers, even if they returned to their starting institution in the subsequent fall term. We do, however, show the proportion of summer swirlers (i.e., transfers among students who started at four-year institutions that happen only in summer followed by a return to the starting four-year institution).

Finally, although NSC data contain demographic information on students, the coverage for these data is incomplete. Consequently, the results summarized in this report do not break out enrollments by race/ethnicity.